Case Report - Volume 2 - Issue 5

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis at first evaluation in smoker undergoing a smoking cessation program

Aldo Pezzuto1*; Antonella Tammaro2; Gerardo Salerno3; Marina Borro2; Elisabetta Carico4

1Cardiovascular-Respiratory Science Department, Sant’Andrea Hospital-Sapienza University, Via di Grottarossa, 1035/39 , 00189,Rome, Italy.

2Department of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Sensory Organs [NESMOS], Sapienza University of Rome, Via di Grottarossa1035, 00189 Rome. Italy.

3Diagnostic Science Department, S Andrea Hospital-Sapienza University, Via di Grottarossa, 1035/39, 00189, Rome, Italy.

4Clinical and Molecular medicine Department, Sapienza University, Via di Grottarossa, 1035/39 ,00189, Rome, Italy.

Received Date : Aug 13, 2022

Accepted Date : Sep 12, 2022

Published Date: Sep 16, 2022

Copyright:© Aldo Pezzuto 2022

*Corresponding Author : Aldo Pezzuto, Sant’Andrea Hospital, Sapienza University, Rome, Via Grottarossa 1035, Italy.Tel: 390633775959

Email:pezzutoaldo@libero.it

DOI: Doi.org/10.55920/2771-019X/1245

Abstract

Smoking is the most significant avoidable risk factor. Responsible of a wide range of diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and respiratory acute and chronic diseases. It is frequently associated with interstitial pulmonary diseases and notably it can be a cause of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In this report we present a case of heavy smoker who developed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: Smoking, pulmonary fibrosis.

Introduction

Tobacco smoke is the leading avoidable cause of mortality worldwide, causing over 5 million deaths annually [1]. A complex mixture of more than 4,000 substances, tobacco smoke induces a chronic condition, increases the risk of death from many types of cancer and causes alterations of multiple organs. These compounds include gaseous and liquid media such as carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen monoxide, hydrocarbon, and nicotine, which is responsible of smoking addiction [2]. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (lPF) is a chronic diffuse interstitial lung disease of unknown origin, characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the lung parenchyma. There is a strong association of smoking with interstitial lung diseases and IPF [3]. Herein we present a case of a patient who was diagnosed IPF during a check for a smoking cessation program.

Case Presentation

On March 30, 2022 a 66-year-old male presented to the outpatients service for smoking cessation, willing to stop smoking. He complained of shortness of breath, exertional dyspnea, dry cough. His respiratory rate was 25 breaths per minute and the pulse rate was 90 beats per minute. The oxygen hemoglobin saturation was 92% at room temperature. The patient was a current smoker with a pack-years of 35, a Fagestrom dependence test of 5 indicating a moderate level of dependence, exhaled carbon monoxide 14 ppm (normal limit = 7). The patient denied any recent travel or sick contacts.

Investigations

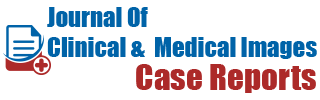

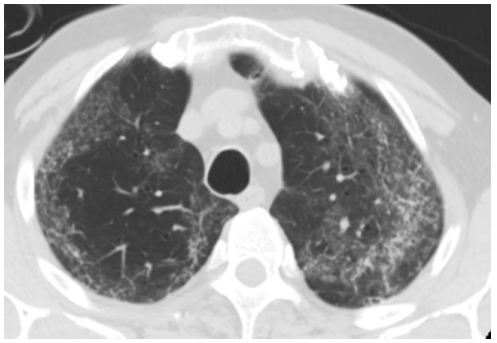

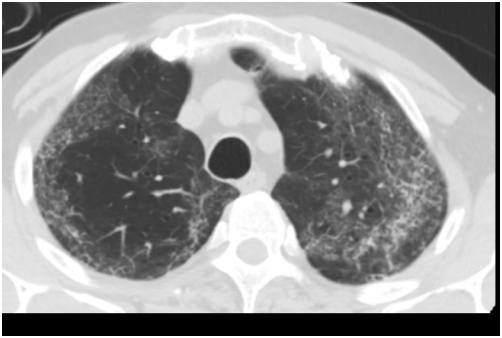

Baseline investigations included blood test , nasal and pharyngeal swab test, spirometry. The full blood picture revealed a white cell count of 13.5 x 103/µl with neutrophilia (9.9 x 103/ µl), C reactive protein (CRP) 9 mg/dl. The oral and nasopharyngeal swab test for rRT-PCR Covid-19 detection was negative. Investigations regarding viral, bacterial and atypical bacteria serological were reported negative. Immune screening was also negative. A computed tomography pulmonary angiogram performed 10 days after the clinical onset, reported ground glass opacities with honeycomb and bronchiectasis that were more pronounced in the upper lobes (Figure 1-3). The spirometry was performed by body pletismography as follows: briefly, flow dynamic volumes were measured with the pneumotacographic method and volumes and resistances with the plethysmographic method. It revealed a restrictive pattern: FEV1<70% of predicted, FVC<65% of predicted, TLC <70% of predicted with an increased level of resistances (120%). A 6 minutes walking test (WT) was also performed, during which the oxygen saturation and the distance covered were recorded showing a reduced peripheral oxygen saturation during 200 m of walking (SpO2 89%).

Treatment and Outcome

The patient underwent smoking cessation by varenicline with the following schedule dosage : capsule 0.5 mg per day for three days, then 0.5 mg twice a day for 4 days, increasing the dosage up to 1 mg twice per day. An oxygen support with nasal cannulae was started as needed, and antibiotic (clarithromycin) was used. The patient quit smoking one month after the beginning of the therapy. Patient’s symptoms quickly improved after smoking cessation with a reduction of cough and exertional dyspnea. The radiological picture did not change.

Figure 1:Upper lobes: ground glass, peripheral reticulation, bronchiectasis

Figure 2: At level of scissure: cystic spaces, bronchiectasis

Figure 3: At level of carina: honeycomb and bronchiectasis

Discussion

This is an interesting case of a patient who presented at the outpatient service for smoking cessation, complaining of dyspnea and cough. Cigarette smoking is associated with the risk of developing interstitial lung diseases and smoking status affects the clinical manifestations of pulmonary fibrosis. Notably smoking increases mortality in IPF compared with never smokers [4]. There is a strong relationship between smoking habit and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis IPF with OR 2.3 in current smokers and 1.6 in former smokers. Notably patients with a pack-year major than 20 are more susceptible to developing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [3]. Smoking along with environmental exposure has been hypothesized to affect the development of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis through different pathways, inducing oxidative stress and stimulating fibroblasts growth factors [5]. The management of the disease includes a respiratory functional evaluation characterized by a restrictive pattern and respiratory failure on exertion [6]. Smoking cessation is very important to slow down the progression of the disease as long as it may hinder the development of resting respiratory failure [7]. Although smoking cessation is not sufficient to slow the progression of the disease, nevertheless it is essential to reduce the inflammatory component and to achieve rapid improvement in symptoms. The use of plethysmography is important to determine bronchial flows and static volumes that could reveal a restrictive pattern [8].

Ethical approval: An informed consent was obtained by the patient

Funding: No funding received

Declaration of interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Unverdorben M, Mostert A, Munjal S, van der Bijl A, Potgieter L, Venter C, et al. Acute effects of cigarette smoking on pulmonary function. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010 : RTP. 2010; 57(2-3): 241-6.

- Tonini G, D’Onofrio L, Dell’Aquila E, Pezzuto A. New molecular insights in tobacco-induced lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2013; 9(5): 649-55.

- Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Stidley CA, Colby TV, Waldron JA. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 155(1): 242-8.

- Kishaba T, Nagano H, Nei Y, Yamashiro S. Clinical characteristics of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients according to their smoking status. J Thorac Dis. 2016; 8(6): 1112-1120.

- Lee CT, Feary J, Johannson KA. Environmental and occupational exposures in interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2022; 28(5): 414-420.

- American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement.American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000; 161(2pt):646-664.

- Pezzuto A, Carico E. Effectiveness of smoking cessation in

smokers with COPD and nocturnal oxygen desaturation: Functional analysis. Clin Respir J. 2020; 14(1): 29-34. doi: 10.1111/crj.13096. - D’Ascanio M, Viccaro F, Calabrò N, Guerrieri G, Salvucci C, Pizzirusso D, Mancini R, De Vitis C, Pezzuto A, Ricci A. Assessing Static Lung Hyperinflation by Whole-Body Plethysmography, Helium Dilution, and Impulse Oscillometry System (IOS) in Patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15: 2583-2589.