Case Report - Volume 2 - Issue 6

Imaging Diagnosis of Retrobulbar Metastasis from Ewing’s Sarcoma in Thigh – Unusual Case Report

Ramadan M. Abuhajar1*; Hania O Alfargany2; Ali S. Amer3

1Radiology Department-Faculty of Medicine, Almergib University;National Cancer Institute-Misurata/Libya.

2Medical Oncology Department- National Cancer Institute-Misurata/Libya.

3Radiology Department, National Cancer Institute, Misurata, Libya.

Received Date : Sep 13, 2022

Accepted Date : Oct 21, 2022

Published Date: Nov 07, 2022

Copyright:© Ramadan M. Abuhajar 2022

*Corresponding Author : Ramadan M. Abuhajar, Radiology DepartmentFaculty of Medicine, Almergib University; National Cancer Institute-Misurata/Libya

Email: raabuhajar@gmail.com

DOI: Doi.org/10.55920/2771-019X/1286

Abstract

Orbital tumors are very rare and we reported a case of retrobulbar metastasis from Ewing sarcomain young adult male patient. He presented to National Cancer Institute-Misrata/Libya with metastatic complications of diagnosed Ewing sarcoma in thigh and he was receiving cycles of chemotherapy. During days of admission the patient complained of right vision loss with proptosis. Imaging was underwent for brain and orbits revealing diagnosis ofright retrobulbar metastasis.

Keywords: Imaging; vision loss; metastasis; retrobulbar; Ewing’s sarcoma; adult.

Introduction

Ewing's sarcoma is the second malignant bone tumor after osteosarcoma among children and adolescents or in a range between 5 and 25 year old according of the other studies. The commonest location of Ewing's sarcoma is the upper limb, lower limb, pelvis, spine and can affect anyone [1,2,3]. The orbital, conjunctival and lacrimal gland malignant tumors areinfrequent and increasing with increasing age, also they are higher in incidence among males than females [4]. The orbital metastasisis extremely rare [2,5]. Orbital neoplasms areaccounting of only 0.1% of all neoplasms in all the human body. Orbital metastasis is estimated to represent 1-13% of all reported orbital tumors [6,7,8,9]. Breast and prostate cancers are the commonest type to metastasize to the orbit followed by bone and lung among female and male adults, whereas Ewing's sarcoma metastasize to the orbits more frequent among children [5]. The clinical symptoms including vision impairment or loss, exophthalmos, vertigo [10]. We reported an unusualcase of retrobulbar metastasis from Ewing's sarcoma in adult.

Case Presentation

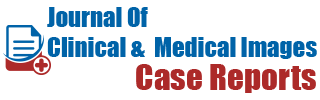

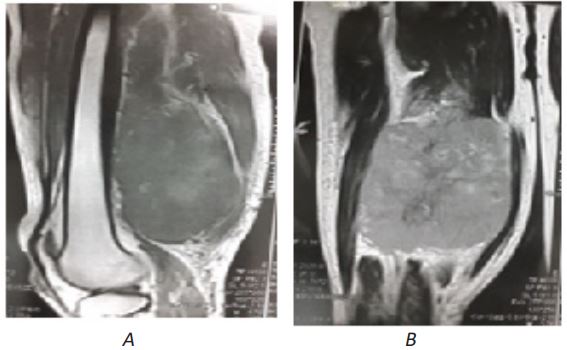

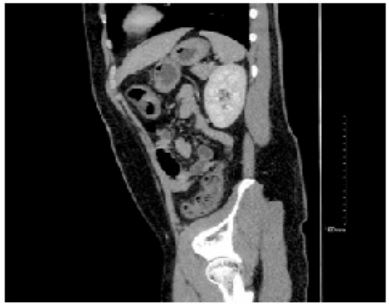

Thirty-first year old male patient presented during admission in National Cancer Institute-Misrata/Libya as a known case of Ewing's sarcoma in the right thigh.Imaging of thigh (Figure 1,2) was underwent before admissionin our Institute and diagnosed as Ewing's sarcoma in the right thighproved histopathologically in 2021.He received cycles of chemotherapy withappearance of mass regression. In the last period imaging was underwent for chest, abdomen and pelvis revealing aggression of the sarcomawith distant metastasis to the lungs, bones, spinal vertebrae and cord (Figure 3,4) as well as to the liver with mediastinal and abdominopelvic lymphadenopathy.

The patient was admitted in our Institutein Aug. 2022 with presentation of paraplegia, sensation loss of urination and defecation, general weakness as complication of distant metastasis and lastlydevelopedright side vision loss and proptosis.

CT scan of brain and orbits (Figure 5) was underwent in the Institute and revealed retro-bulbar soft tissue mass lesion in extraconal compartments of the right orbit and enhanced with contrast media. Nopathological changes in the brain parenchyma, normal posterior fossa and brain stem, normal appearance of ventricular system and no shift of midline structures.MRI of brain and orbits (Figure 6,7,8) was underwent also in the Institute revealing right retro-bulbar enhanced mass lesion under the inferior rectus muscle of the eye ball measuring about 2.8 x 1.4 cm. The mass extended through the optic canal and superior orbital fissure, compressing and displacing the distal optic nerve superiorly with proximal encasement of the optic nerve as well as encasing the oculomotor nerve. The imaged retrobulbar mass is one of a distant metastatic lesions from the known Ewing's sarcoma in the thigh which is markedly rare case report. Normal grey-white matter interface with no lesion or any changes in the brain parenchyma, no intra or extracerebral nodules, hemorrhagic changes or any collection. Normal cerebellum, brain stem and cervico-medullary junction. Normal size, shape and position of the ventricular system with no midline shifting or deformity.

Figure 1. ECG findings revealed concave up ST elevation and PR segment depression that are common in the setting of acute pericarditis.

Follow Up

On follow-up with his primary care physician, he reported an absence of chest pain and diarrhea. The CRP level had normalized.

Figure 2: Abdominal CT revealed pancolitis with diffuse colonic wall thickening and edema.

Figure 3: Sagittal view of the CT scan from the thoracic cavity demonstrating minimal pericardial effusion.

Discussion

The most common cause of diarrhea is infectious etiologies. While the most common infection is viral gastroenteritis, bacteria such as Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Shigella are the most common cause of acute diarrhea [1]. One of the leading pathogens that cause gastroenteritis in developed countries is the Campylobacter species. Campylobacteriosis has early and late complications that can be deleterious. For instant, urticaria, erythema nodosum, cholecystitis, peritonitis, and abdominal aortic septic pseudoaneurysm. The late course of the disease presents as reactive arthritis and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Campylobacter infection may progress to bacteremia in immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals (2). Pericarditis and myocarditis can be associated with a late complication of campylobacter gastroenteritis, as demonstrated in our patient [3]. The development of cardiac manifestations presents most often involves young adults or teenagers. As in most gastroenteritis illnesses, symptoms begin with fevers, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, after which symptoms of concurrent chest pain, discomfort, or tightness ensue within 48-72 hours [5]. Therefore, a reported history of chest discomfort following bouts of diarrhea should prompt physicians to include Campylobacteriosis in their differential [4]. The pathophysiology of perimyocarditis secondary to Campylobacter gastroenteritis is not fully understood. Still, the combination of the number of organisms consumed, the virulence of the infecting strain, and the host immunity are all crucial factors in the patient’s clinical presentation. Several factors are beginning to be just understood, and two proposed models have been reviewed in the literature. One model suggested that the pathogen or toxin-induced may be responsible for the acute presentation of the carditis within 48-72 hours. The alternative model offered that the immunological response such as systemic circulation of immune complexes or cytotoxic T Cell attack presents with the later presentation of the cardiac embodiments [6-9].

Regardless of the proposed pathogenies of the disease, almost all the immunocompetent patients with gastroenteritis secondary due to campylobacter infection in the literature have not been reported to experience bacteremia with the disease. However, this doesn’t exclude the likelihood of the pathogen harboring transient bacteremia as its mechanism of action [10]. Lastly, because most Campylobacter infections are self-limited and have limited efficacy of antimicrobials, antibiotic therapy is only recommended for individuals with severe disease. For instance, patients with bloody stools, a high temperature, an extraintestinal infection such as myocarditis, pericarditis or perimyocarditis, increasing or recurrent symptoms, or symptoms that persist for more than a week are considered to have a severe illness [11].

Conclusion

Gastroenteritis due to Campylobacter infection can be mild, self-limited, and often treated with a supportive case. However, the physicians need to recognize progression to cardiac manifestations of Campylobacteriosis, such as myocarditis and pericarditis, as severe manifestations as treatment varies. Meanwhile, the exact pathogenesis of the disease is still under review, and physicians’ awareness of the progression of the disease will allow a timely, focused treatment.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Funding Sources: None.

References

- Dryden MS, Gabb RJ, Wright SK. Empirical treatment of severe acute community-acquired gastroenteritis with ciprofloxacin. Clin Infect Dis. 1996 Jun; 22(6): 1019-25. [PMID: 8783703 DOI: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1019].

- Spapen J, Hermans H, Rosseel M, Buysschaert I. Campylobacter jejuni-related cardiomyopathy: Unknown entity or yet underreported? Int J Cardiol. 2015 Nov 1; 198: 24-5. [PMID: 26149333 DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.110] [Epub 2015 Jul 3]

- Hannu T, Mattila L, Rautelin H, Siitonen A, Leirisalo-Repo M. Three cases of cardiac complications associated with Campylobacter jejuni infection and review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005 Sep; 24(9): 619-22. [PMID: 16167138 DOI: 10.1007/s10096-005-0001-2].

- Lai T, Yadav R, Schrale R. Mimicking myocardial infarction: localized ST-segment elevation in Campylobacter jejuni myopericarditis. Intern Med J. 2009 Jun; 39(6): 422-3. [PMID: 19580626 DOI: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.01930.x].

- Hessulf F, Ljungberg J, Johansson PA, Lindgren M, Engdahl J. Campylobacter jejuni-associated perimyocarditis: two case reports and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 14; 16: 289. [PMID: 27297408; PMCID: PMC4907281 DOI: 10.1186/s12879-016-1635-7].

- Florkowski CM, Ikram RB, Crozier IM, Ikram H, Berry ME. Campylobacter jejuni myocarditis. Clin Cardiol. 1984 Oct; 7(10): 558-9. [PMID: 6488601 DOI: 10.1002/clc.4960071008].

- Uzoigwe C. Campylobacter infections of the pericardium and myocardium. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005 Apr; 11(4): 253-5. [PMID: 15760422 DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01028.x].

- Pena LA, Fishbein MC. Fatal myocarditis related to Campylobacter jejuni infection: a case report. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2007 Mar-Apr; 16(2): 119-21. [PMID: 17317547 DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2006.09.007].

- Alzand BS, Ilhan M, Heesen WF, Meeder JG. Campylobacter jejuni: enterocolitis and myopericarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2010 Sep 24; 144(1): e14-6. [PMID: 19168238 DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.12.101] [Epub 2009 Jan 26].

- Skirrow MB, Jones DM, Sutcliffe E, Benjamin J. Campylobacter bacteraemia in England and Wales, 1981-91. Epidemiol Infect. 1993 Jun; 110(3): 567-73. [PMID: 8519321; PMCID: PMC2272297 DOI: 10.1017/s0950268800050986].

- Ruiz-Palacios GM. The health burden of Campylobacter infection and the impact of antimicrobial resistance: playing chicken. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Mar 1; 44(5): 701-3. [PMID: 17278063 DOI: 10.1086/509936] [Epub 2007 Jan 25].