Case Report - Volume 3 - Issue 1

Coronary arteriovenous fistula with a giant coronary sinus aneurysm

Diala Steitieh1*; Krista Vadaketh2; Ruth Kagan2; Jiazhen Li2; Quynh Truong1; Ashley Beecy1

1Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

2Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

Received Date : Nov 17, 2022

Accepted Date : Dec 29, 2022

Published Date: Jan 19, 2023

Copyright:© Diala Steitieh 2023

*Corresponding Author : Diala Steitieh, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

Email: dis2012@nyp.org

DOI: Doi.org/10.55920/2771-019X/1352

Introduction

Coronary arteriovenous fistulas (CAFs) are a rare congenital malformation of the coronary arteries, with a prevalence of 0.002% in the general population [1]. These fistulas result from a communication between one or more coronary arteries and an adjacent cardia chamber or great vessel [2]. Most CAFs are small and asymptomatic, however when they enlarge they can cause symptoms of coronary steal or of left-to-right shunting, leading to angina, shortness of breath, myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure [3]. Syncope is a very rare presenting symptom of CAFs however, and to our knowledge there have been no reports of syncope resulting from right ventricular outflow obstruction. We present a unique case of a patient with a CAF between the left main/left circumflex coronary artery and the coronary sinus (CS), prolapsing into the right atrium and causing right ventricular outflow obstruction and syncope.

Case Report

A 77-year-old woman with history of breast cancer (in remission), asthma, and premature birth presented with dyspnea on exertion and decreased exercise tolerance. She was noted to be tachycardic, and CT chest revealed a large pericardial effusion for which she underwent therapeutic and diagnostic pericardiocentesis. Serous fluid was drained, and was transudative in character with negative cytology and infectious workup. A complete echo was then obtained, revealing a smaller pericardial effusion but with a large right atrial cystic structure and dilated coronary sinus (CS). A cardiac CT was ordered for further characterization and was notable for an arteriovenous fistula between the left main/left circumflex coronary aneurysm and giant coronary sinus aneurysm (Figure 1). The giant coronary sinus aneurysm measured 4.8cm, protruded into the right atrium, and prolapsed with the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

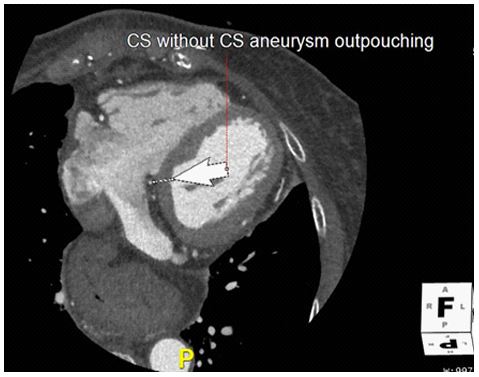

The following day while awaiting further workup she was noted to have a syncopal event while ambulating, with no correlating events on telemetry. Left and right heart catheterization was performed and revealed a severely dilated coronary sinus aneurysm prolapsing into the right atrium, and a coronary artery fistula of the left circumflex to coronary sinus with massive coronary dilation (Figure 2). There was no obvious coronary artery disease. Qp to Qs ratio was 1.7:1. TEE was performed for further visualization of anatomy, which was suggestive of obstructive aneurysm into the tricuspid valve, as well as an atrial septal defect (Figure 3). The patient underwent successful coronary sinus aneurysm repair, where the circumflex to coronary sinus fistula was ligated. Her post operative CT showed the coronary sinus without the coronary sinus aneurysm outpouching (Figure 4). She had no further episodes of syncope or shortness of breath while recovering, and was discharged to rehab shortly thereafter.

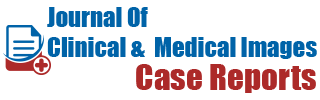

Figure 1: Cardiac CT

(A) Multiplanar reformatted images showing the coronary sinus aneurysm outpouching protruding into the right atrium during systole. (B) Reformatted images of the coronary sinus aneurysm during diastole traversing the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. (C) Volume-rendered 3-dimensional image of the LM/LCx aneurysm (yellow arrow) with a fistulous connection to the coronary sinus aneurysm (red arrow) and outpouching (green arrow), also seen is the LAD (blue arrow).

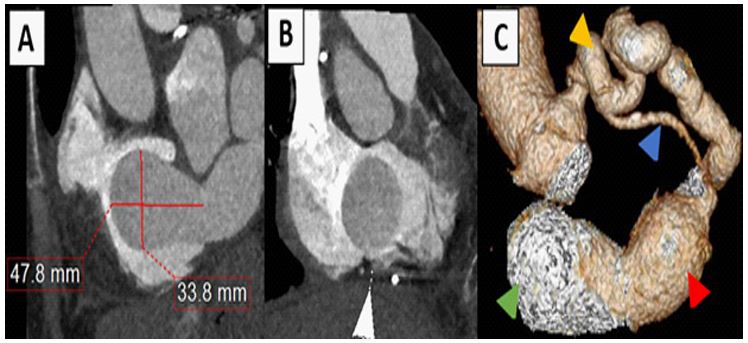

Figure 2: LHC of fistula

Severely dilated coronary sinus aneurysm prolapsed into the right atrium with to and fro flow.

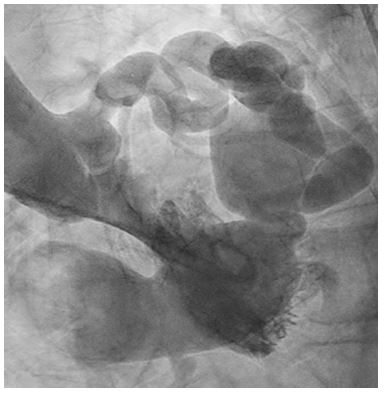

Figure 3: TEE

Mid-esophageal RV focused view demonstrates the coronary sinus aneurysm (arrow) prolapsing into the tricuspid valve.

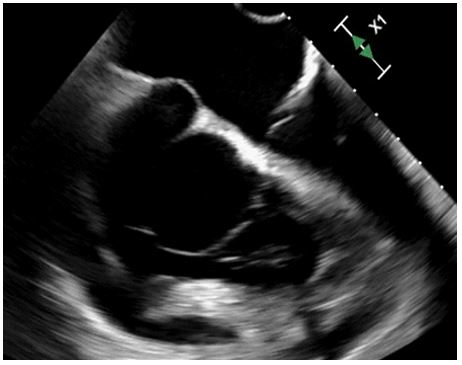

Figure 3: Post operative CT

Post-operative multiplanar reformatted images of the CS aneurysm resection.

Discussion

There are several methods to classify CAF, one of the common ways is though identifying the drainage site of the CAF. The drainage of CAF can either be into a cardiac chamber (coronary cameral fistulas) or drainage into lower pressure venous systems (coronary arteriovenous fistulas, CAF) [4,5]. Only 7% of CAF drain into the coronary sinus [6] specifically. To date, there are no published case reports of co-existing left main/ left circumflex aneurysms with a coronary sinus fistula. The gold standard for the diagnosis of coronary artery fistulas is through cardiac catheterization, where selective coronary angiography can establish the sites of original and termination of a CAF, as well as the blood flow through it [7]. More recently however coronary computerized tomography angiography (CTA) and MR angiography have provided an alternative means of determining the anatomy of a CAF [8]. In addition to being non-invasive coronary CTAs have a higher sensitivity for the diagnosis of CAF as compared to angiography [9]. In our patient’s case, her CTA best demonstrated the arteriovenous fistula and consequent giant coronary sinus aneurysm that prolapsed into the right ventricle (a detail that would have been difficult to assert on catheterization alone). Echocardiography provides an alternative method of diagnosis, and microbubble contrast injection can help identify CAF and their course, although the limited field of view on echo can limit the assessment of a fistulous tract and other extracardiac structures [8]. Large fistulas may produce symptoms even in infancy, however more than half of adult patients may remain asymptomatic. Symptoms in adults include congestive heart failure, dyspnea, arrhythmias (due to chamber dilation) and angina (due to coronary steal phenomenon) [10-12]. Our patient presented uniquely with a large pericardial effusion. The most common etiology of pericardial effusions in the context of CAF is due to fistula rupture [13], where the pericardial effusion has a bloody appearance (hemopericardium). Our patient however had a serous transudative effusion, we therefore hypothesize that her effusion developed secondary to elevated filling pressures of the coronary sinus, directly related to the CAF. Moreover syncope can rarely be seen in some patients with CAF, and has been described secondary to extensive coronary ischemia with consequent complete heart block [14] as well as consequent ventricular fibrillation [15]. Our case is unique however in the presence of a syncopal episode despite having no arrhythmias. We hypothesize that the patient’s syncopal episode was secondary to transient right ventricular outflow tract obstruction by the prolapsing coronary sinus aneurysm. Various algorithms have been recommended to determine surgical versus transcatheter approach treatment of CAF. Due to the prolapsing nature of the aneurysm in our patient however, she was advised to undergo surgical repair, and has been doing well since that time with no recurrent pericardial effusions or syncopal events.

Conclusion

The present case describes a unique presentation of CAFs, with the formation of a giant coronary sinus aneurysm and consequent pericardial effusion and syncope, likely due to transient right ventricular outflow obstruction by a prolapsing aneurysm. The case highlights the various and unusual ways in which a CAF may present.

Sources of Funding : None

Disclosures : None

References

- Ogden JA. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries [Internet]. The American Journal of Cardiology. Am J Cardiol; 1970; 25: 474-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/5438244/

- Ata Y, Turk T, Bicer M, Yalcin M, Ata F, Yavuz S. Coronary arteriovenous fistulas in the adults: natural history and management strategies. J Cardiothorac Surg [Internet]. 2009; 4(1): 62. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2777143/

- Yun G, Nam TH, Chun EJ. Coronary artery fistulas: Pathophysiology, imaging findings, and management. Radiographics [Internet]. 2018; 38(3): 688-703. Available from: https://pubs. rsna.org/doi/10.1148/rg.2018170158

- Fujimoto N, Onishi K, Tanabe M, Koji T, Omichi C, Kato S, et al. Two cases of giant aneurysm in coronary-pulmonary artery fistula associated with atherosclerotic change. Int J Cardiol [Internet]. 2004; 97(3): 577-8. Available from: https://pubmed. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15561356/

- Shriki JE, Shinbane JS, Rashid MA, Hindoyan A, Withey JG, Defrance A, et al. Identifying, characterizing, and classifying congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. Radiographics [Internet]. 2012; 32(2): 453-68. Available from: https://pubs. rsna.org/doi/10.1148/rg.322115097

- Dodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Backer CL. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: Anomalies of the coronary arteries. In: Annals of Thoracic Surgery [Internet]. Elsevier Inc.; 2000 [cited 2022 Oct 18]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10798435/

- Hofbeck M, Wild F, Singer H. Improved visualisation of a coronary artery fistula by the “laid-back” aortogram. Br Heart J [Internet]. 1993; 70(3): 272-3. Available from: /pmc/articles/ PMC1025308/?report=abstract

- Yun G, Nam TH, Chun EJ. Coronary artery fistulas: Pathophysiology, imaging findings, and management. Radiographics [Internet]. 2018; 38(3): 688-703. Available from: https://doi. org/10.1148/rg.2018170158

- Rao SS, Agasthi P. Coronary Artery Fistula [Internet]. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32644617

- Reddy G, Davies JE, Holmes DR, Schaff HV, Singh SP, Alli OO. Coronary Artery Fistulae [Internet]. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2015; 8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26510560/

- Gowda RM, Vasavada BC, Khan IA. Coronary artery fistulas: Clinical and therapeutic considerations [Internet]. International Journal of Cardiology. Int J Cardiol; 2006; 107: 7-10. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16125261/

- Maleszka A, Kleikamp G, Minami K, Peterschröder A, Körfer R. Giant coronary arteriovenous fistula: A case report and review of the literature [Internet]. Zeitschrift fur Kardiologie. Z Kardiol; 2005; 94: 38-43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/15668829/

- Shin-ichiro O, Toshinori U, Tomoya K, Takashi T, Shinsuke T, Shuzo M, et al. Coronary arteriovenous fistula presenting as chronic pericardial effusion. Circulation Journal [Internet]. 2022; 66(8): 779-82. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/12197607/

- Alameh A, Daoud A, Jabri A. Abstract 14694: Coronary Artery Fistula Presenting With Complete Heart Block and Syncope. Circulation [Internet]. 2020; 142(Suppl_3). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/circ.142.suppl_3.14694

- Meric M, Yuksel S. Diffuse Coronary Artery Fistula Leading to Syncope and Treated with Transcatheter Coil Occlusion and a Defibrillator: A Case Report. Medical Principles and Practice [Internet]. 2019; 28(5): 493-6. Available from: https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30995647/