Research Article - Volume 3 - Issue 1

Perception and coping strategies among patients with non-specific chronic neck pain

Ojoawo Adesola Ojo*1; Olubunmi Precious Daniel1; Awotipe Adedayo Ayotunde2; Adeyemi Timothy3

1Department of Medical Rehabilitation, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria.

2Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Medical Rehabilitation, University of Medical Sciences, Ondo.

3Department of Physiotherapy, Bowen University, Iwo.

Received Date : Dec 08, 2022

Accepted Date : Jan 06, 2023

Published Date: Jan 28, 2023

Copyright:© Ojoawo Adesola Ojo 2023

*Corresponding Author : Ojoawo Adesola Ojo, Department of Medical Rehabilitation, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile Ife, Nigeria.

Email: aoojoawo@oauife.edu.ng

DOI: Doi.org/10.55920/2771-019X/1359

Abstract

Objectives: The study investigated the perception of causes and the coping strategies employed by the patients with non-specific chronic neck pain (NSCNP).

Methods: Fifteen respondents (5 males, 10 females) with NSCNP participated in the study. Qualitative interview was conducted using a three-section modified structured interview guide by Lansbury. This was captured in the themes, categories and sub-categories in relation with the respondents’ coping strategies with neck pain. The two main themes from the categories were perception of neck pain and coping strategies. The data were analyzed using thematic content analysis.

Results: Considering the themes on perception, half of the respondents perceive that neck pain was caused by stress and work-related activities and 26%perceived that neck pain was caused by poor sleeping posture. On Coping strategies theme, 70% reported the used prayer, 53% approached it conventionally and about15% ignored the pain.

Conclusion: The main coping strategies as described by the 15 patients with NSCNP in this study was prayer followed by conventional intervention. Average number of patients perceived that neck pain was caused by stress and work related activities.

Keywords: Neck pain; prayer; coping; perception; qualitative study.

Introduction

Neck pain occurs commonly throughout the world and causes substantial disability and economic cost with a huge impact on individuals the families, communities, healthcare systems and businesses [1]. Neck Pain is defined by the Global Burden of health 2010 Study as "pain in the neck with or without pain referred into one or both upper limbs that lasts for at least one day” [2]. Risk factors for neck pain share similarities with other musculoskeletal conditions such as genetics, psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety, poor coping skills, somatisation), sleep disorders, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle [3] which include a history of neck pain [4] trauma (e.g., traumatic brain and whiplash injuries) and certain sports injuries (e.g., wrestling, ice hockey, football) [3]. Although certain occupations such as office and computer workers, manual labourers, and health care workers, have been found in some studies to have a higher incidence of neck pain, the major workplace factors associated with the condition are low job satisfaction and perceived poor workplace environment [3].

Most acute episodes resolve spontaneously, more than a third of affected people still have low grade symptoms or recurrences more than one year later [5]. The strongest evidence in the management of neck pain is exercise [5]. Study of patient experience and management of neck pain in general practice found that many self-managed their pain with techniques like massage and over-the-counter medication [6]. Coping with pain plays an important role in the healing process [7,8]. Patients with chronic neck pain need strategies to manage their plan and its impact, because coping is not restricted to one dimension of human functioning (cognitive, affective, behavioral and physiological) [7]. Rosentiel and Keefe grouped strategies for coping with pain into six categories: catastrophizing, ignoring pain, diversion, reinterpreting pain, praying and hoping [9]. But the perception of patients with neck pain, and how thepain affect the activities of daily living and the strategies employed by patients to cope with neck pain in this environment have not been well investigated. The aim of the study was to evaluate the patients with non-specific neck pain on their perception of the causes of the pain and how they have been coping with it using qualitative approach. It could be hypothesized that perception of patients of the causes would be on ergonomics and the major coping strategy would be medication.

Methods

Respondents: The respondents for this study were patients with neck pain receiving treatment at Physiotherapy Clinic of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex.

Inclusion Criteria: The inclusion criteria were; (i) patients with non-specific chronic neck pain between 18 and 65-years-old and, (ii) patients with neck pain who were literate in english or yoruba languages.

Exclusion Criteria: Patients with neck pain that had cognitive impairment and other underlying pathologies. These were ascertained by history of the condition given by the patients and some examinations including the X-ray to rule out the causes.

Study Design: This is a qualitative study design with face to face interview of the respondents. Sampling Technique: Purposive sampling technique was used for choosing respondents eligible for this study. Sample Size Determination: A selection of 15 respondents was made based on previous literature [10]. Cresswell suggested 5-25 informants for a qualitative study, but a total of 15 respondents were recruited for this study [11]. The data collection was stopped when the information from the respondents got to a saturated point.

Site of the study: This study was carried out at physiotherapy department, obafemi awolowo university hospitals complex, ile-ife.

Instruments: A tape recorder was used for the recording of interview sessions with the respondents in a language they understand (English/Yoruba), using the modified structured interview guide on coping strategies by Lansbury [12]. The structured interview guide contained three sections. Section A contained some questions on sociodemographic information of the patients, such as age, sex, educational status, marital status, and nature of work. Section B contained the numerical pain rating scale used to assess the intensity of the pain. The scale ranged from 0 to 10 (0 = no pain or discomfort, 2 = little or insignificant pain, 4 = moderate or not severe discomfort, 6 = serious discomfort, 8 = very serious discomfort, 10 = excruciating pain).

Section C contained questions about the pain such as the duration of the patient’s pain, the patient’s perception about the pain, pain interference with the patient’s life, coping strategies with the pain, the source of most support for the patient in coping with the pain, other management methods for coping with pain apart from physiotherapy, the management they thought to work effectively for them, and barriers to their pain management. The coping strategies questionnaire was found to be specifically and importantly related to the chronic pain inventory in all subscales [13]. For reliability, the coping strategies questionnaire as a whole scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0 .94 and an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.86 - 0.98) [14].

Procedure

A cross-sectional study was conducted on a total of 15 patients with non-specific chronic neck pain who were recruited using a purposive sampling method. Ethical approval was obtained (IRC/IEC/0004553, NHREC/27/02/2009a) from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals’ Complex, Ile-Ife.

Respondents who met the inclusion criteria were given information about the interview by the researcher and verbal consent was obtained from each respondent before the interview. The interviews took place at Physiotherapy Clinic of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals’ Complex, Ile-Ife. Each interview lasted approximately 20 minutes and was recorded with a tape recorder. Written consent was also obtained at the interview session.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of mean, frequency distribution was used to summarize the socio-demographic variables of the informants. Data analysis was done using the thematic content analysis. The following steps were taken: I was able to familiarize with the data, preliminary codes were assigned to the data in order to describe the content, the codes were scrutinized to identify the patterns of the themes in different interview, the themes were reviewed, defined and named, which then produce the report. All the interviews were conducted and recorded by the researcher and transcribed verbatim. Respondents was given initials that are not related to their original names. As the data collection proceeded, themes were identified and analyzed by repeated study of the scripts by the researcher and analyst. When all the data have been collected and coded, the researcher and the analyst then review and agree on the final themes and data was analyzed using thematic content analysis. Related information was categorized, and each category was compared with other categories.

Results

Coding for the analysis

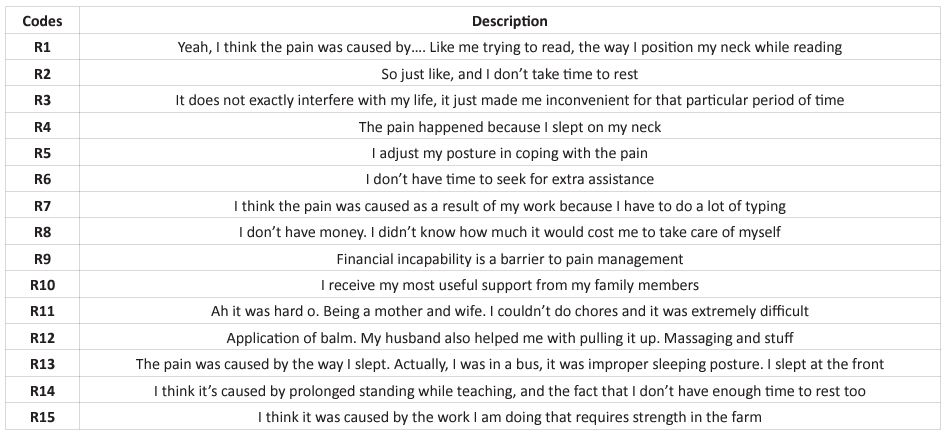

The coding has 15 items, PI to P15, these was used to analyze the comments of the respondents in answering to the questions they were asked. The coding was stated in the table below

Table 1: Coding for the analysis.

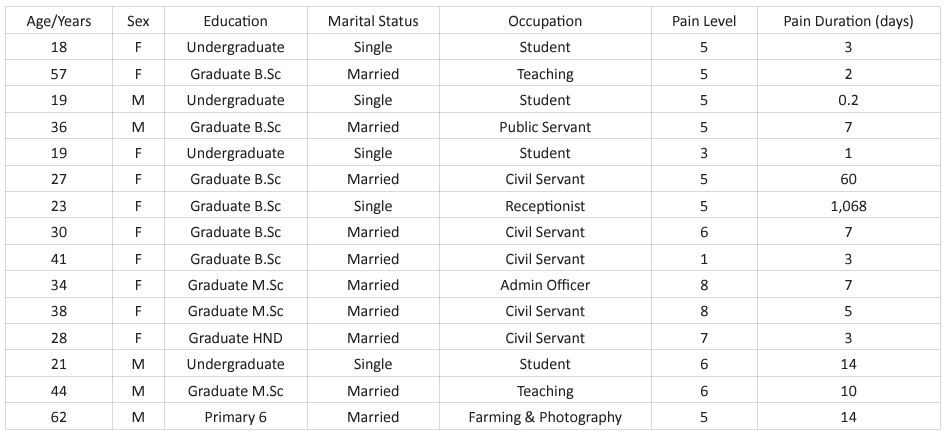

Socio-demographic Data and Clinical Features of the Respondents

Table 2: Socio-demographics and clinical feature of the respondents

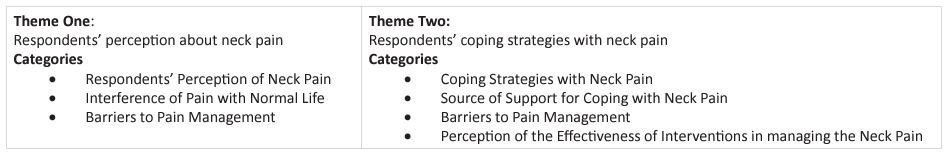

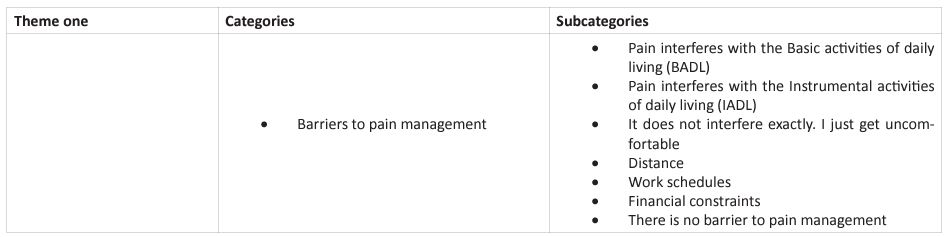

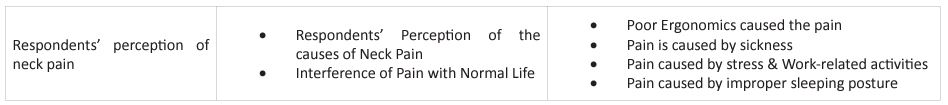

Theme one: Respondents’ Perception of Neck Pain

This theme describes the respondents’ perception of the causes of neck pain, the interference of the pain with their normal life and their barriers to pain management. The respondents perceive their pain to be caused by different illnesses, situations, and circumstances. Most of the respondents indicated that their pain interferes with their normal life, and in seeking for interventions in managing their neck pain, they encountered some barriers. This was captioned by one of the respondents.

“I think the pain was caused as a result of my work because I have to do a lot of typing”, (R7).

This explains that the respondent’s pain was caused as a result of work-related activities.

“At times, if I want to bend down, I won’t be able to do it, and if I want to sleep, I won’t be able to place my neck very well or if I want to dress up, it will be giving me pain, and if I want to bend down to do something, I won’t be able to stretch my body very well” (R2).

The above quote describes that the pain interfered with the respondent’s normal life i.e., the basic activities of daily living. Another respondent described her barrier to pain management,

“I don’t have money. I didn’t know how much it would cost me to take care of myself” (R8).

This reveals that financial constraint is one of the barriers to pain management. The foregoing theme is explained with categories and sub-categories relating to the respondents’ perception of neck pain in (Table 3).

Table 3: Representation of themes and categories.

Respondent Perception of the causes of neck pain

The concept of the pain seems to be understood by majority of the respondents as a result of stress and work-related activities (Table 4). For example, a respondent stated,

“Well, you know when I have too much of work, too much of activities. So just like, and I don’t take time to rest” (R2),

“I think it’s caused by prolonged standing while teaching, and the fact that I don’t have enough time to rest too” (R14) and

“I think it was caused by the work I am doing that requires strength in the farm”. (R15)

Some respondents attributed their pain to improper sleeping posture. For example, a respondent said,

“The pain was caused by the way I slept. Actually, I was in a bus, it was improper sleeping posture. I slept at the front” (R3).

Another respondent asserts that,

“The pain happened because I slept on my neck” (R5).

And few others (13.3%) attributed their pain to sickness, a respondent said,

“I think it (the pain) was caused by… I had fever, so it was familiar” (R8), and

“According to my physician, he said it was actually Typhoid and some other malaria symptoms” (R13).

Another respondent concluded that the pain was caused by poor ergonomics and stated that,

“Yeah, I think the pain was caused by…. Like me trying to read, the way I position my neck while reading” (R1).

Interference of pain with normal life

There was almost a consensus that neck pain interferes with the normal life of the respondents. The respondents narrated that their pain altered their normal living and hindered their performance in most domains of basic and instrumental activities of daily living (Table 3). Some of the excerpts confirm the foregoing.

“It interferes with my basic activities of daily living in a way that while I'm trying to put on my clothes or I'm trying to dress up, I have to position my neck in a particular way, so I’ll be able to wear my clothes very well” (R1),

“Ah it was hard o. Being a mother and wife. I couldn’t do chores and it was extremely difficult” (R11),

“I was unable to turn the neck, while teaching, so it was very difficult for me actually” (R14).

With respect to affectation of work productivity, the respondent stated that,

“It doesn’t really interfere with my life, but I noticed that my work output has been reduced. It is not the way it used to be” (R7).

Some of the respondents recounted that the neck pain didn’t exactly interfere, it just makes them uncomfortable, “it does not exactly interfere with my life, it just made me inconvenient for that particular period of time” (R3).

Barriers to seeking help for pain

The respondents expressed different types of barriers in seeking help and support to cope with their pain. While some of the respondents expressed absolutely no worries, others feel that long distance before getting treatment, financial constraints and tight work schedules are barriers to seeking health care. The following excerpts confirm the above-mentioned.

“Just accessibility to facility that can actually help me. Like a medical facility because of the time” (R4)

“I don’t have time to seek for extra assistance” (R6)

“My environment was uncivilized, total local and down. The environment was not something I was used to. I had no access to a qualified medical centre, just local drug providers” (R13) and

“I don’t have money. It is the money exactly that’s the barrier. There was a time that when they prescribed some drugs for me, and I didn’t have enough money to buy those drugs. So, that’s just it” (R15).

Table 4: Respondents’ perception of neck pain.

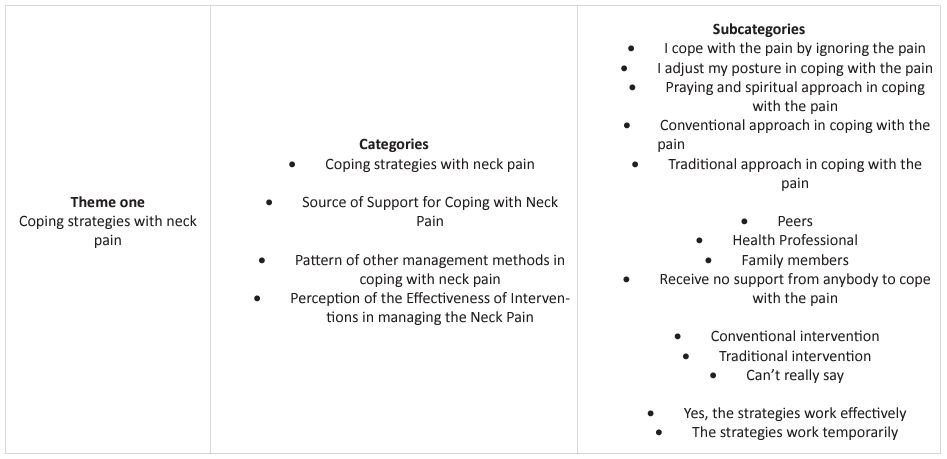

Theme Two: Coping Strategies among respondents with neck pain.

This theme identifies the various coping strategies of patients with neck pain, the source of support for coping with the neck pain and their perception of the effectiveness of interventions in the management of neck pain (Table 4). These were further explained in the categories. Coping strategies of patients with Neck pain (Ignore, Conventional approach, Postural adjustment, Traditional approach & Praying).

The respondents in this study expressed different types of ways they cope with neck pain. Mostly, their coping practices were centered on conventional approach and postural adjustment. Some of the excerpts reveal these practices.

“I use drugs – Paracetamol, Ibuprofen. And there is this cream I use to massage the neck with Neurogelsic. It was my friend that gave me” (R7),

“I took pain killers and then I visited the hospital” (R10), and “Thank God for my husband o. I used strong pain relief. I think I used Diclofenac or so” (R11).

To buttress their postural adjustment practices, some of the respondents recount,

“I didn’t apply anything. I just adjusted my sleeping position properly” (R4).

Few of the respondents seem to cope with their pain by ignoring the pain, while other seems to cope through traditional approach. “I just ignore it. I ignore the pain most times” (R1),

“I just ignored it cos I felt it will go since it was as a result of the fever. I knew fully well that the pain will go when the fever goes” (R8).

And to buttress the traditional approach practices, a respondent stated that, “My mum went into the bush and got me some local herbs which we cooked and ate...” (R13).

However, a respondent resorted to praying and spiritual approach, as a coping strategy for neck pain, alongside with the conventional and traditional approach.

I use “grounded ginger since it’s due to the sore throat, pain relief and prayer because only prayer can make every other thing work” (R12).

Source of support for coping with neck pain

The findings of this study showed that most patients with neck pain never received any support from anybody while other patients received support from varying sources ranging from family, peers and health professionals. No support in coping with the pain was mostly reported by the patients in this study (Table 5). The following excerpts confirm the absence of needed assistance. “I’m the only one managing my pain, there is no one supporting me” (R7), and “There is nobody ooo. It’s God’s help we are enjoying” (R15).However, some of respondents got support from the family members and few of the respondents got support from the Health professionals. “My mum was my physician. She did everything” (R13).

Pattern of other management methods in coping with neck pain

The pattern of interventions used for coping with neck pain were basically Conventional and traditional interventions. While some of the respondents claim to use conventional approaches only, others reveal their traditional practices. For example, some say, “Application of balm. My husband also helped me with pulling it up. Massaging and stuff” (R11),“I ensure I slept well, and I also used balm. I also did body massages” (R13) and “Like I said earlier, I use drugs” (R7). Others reveal that they “just use warm water to touch the place, that’s all” (R2). Another respondent states, “I use some herbal drugs” (R15). However, a good number of the respondents admit to no practice other than the prescribed interventions.

Perception on effectiveness of interventions for coping with neck pain

Most of the respondents were involved in mixed practices for their neck pain, and as such, have perception that bother on their practices. For example, some say

“Yes, it works effectively for me, because after ignoring it, I discover that with time, I won't feel any pain” (R1),

“Hmmmmm… Yes, it works effectively for me. Most especially the advice that I should take time to rest, after too much of stress or activities, I should take time to rest, that’s what my nurse use to tell me, and I do it, and it really works” (R2).

Yet some respondents still spoke about their perception of the conventional interventions they received. These excerpts buttress the above assertion.

“They (drugs) relieve the pain temporarily, but when everything wears off, the pain is back” (R7), “Yes, yes. It (balm) works effectively. I saw positive changes” (R13).

One of the respondents spoke about his perception of the traditional interventions he received,

“It works sometimes. And when it was not working again, that’s why I came to the Clinic to seek for medical counsel.” (R15).

Table 5: Respondents’ coping strategies with neck pain.

Discussion

This study investigated the coping strategies among patients living with neck pain in Physiotherapy Clinic Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife.

The result of this study showed that more than average of the respondents were within 21-40 years of age while more than twenty-six percent were aged 41 and above, with twenty percent below the age of 20 years. This supports a previous study by [15], that approximately half of all individuals will experience a clinically important neck pain episode over the course of their lifetime.

From the investigations carried out, more than forty-six percent of the respondents classified the experienced level of neck pain as moderate, forty percent reported the pain to be high, more than thirteen percent reported to be low, because most of the respondents described that the pain started very little, and then, it progressed to moderate pain. More than sixty-six percent of the respondents said the pain duration was less than seven days, twenty percent of the respondents said pain was between 8-14 days and about thirteen percent of the respondents said pain lasted for 15 days and above. This findings on the duration of neck pain contradicts the study carried out by [16], that 30% of patients with neck pain will develop chronic symptoms and 37% of individuals who experience neck pain will report persistent problems for at least 12 months. The reasons for the findings in our study could be deduces to the assumption that possibly participants in this study have access to medication or to one form of intervention or the other during the pain episode. Again if the patient has developed a very strong coping strategy that will not allow the pain to last longer.

From the analysis of the socio-demographic data, more females were seen to have neck pain than males, which corroborates with the previous study carried out by [1,15-17]. The high incidence of neck pain among females in this study may not be unconnected to the various home cores couple with other office activities always embarked by women. Repetitive movement of turning especially in daily activities may be one of the predisposing factors to neck pain among women. It is also observed that neck pain is seen to be common among civil servants, which supports the previous study by [17], that there is a higher incidence of neck pain among office and computer workers, because they spend many hours sitting stationary at their desks on computers. When sitting for prolonged periods, it’s common to slouch and adopt a forward neck position. This increases compression through the joints in the neck and causes an overload of the neck muscles lying at the back, thereby eliciting pain in the neck. Ojoawo et al reported high prevalence of neck pain among both academics and non-academics among a Nigerian University staff [18]. The point highlighted for the prevalence was due to usage of computer for which individuals will need to be continually flexing the cervical region.

The results of this study showed that more than average of the respondents perceive that neck pain was caused by stress and work-related activities. They believed that it occurred as a result of the many activities they were doing and the fact that they don’t have enough time to rest, while some of the respondents felt neck pain was caused by poor sleeping posture, more than thirteen percent said it was caused by sickness and only about seven percent said it was caused by poor ergonomics. Doing a specific work repeatedly under a poor ergonomics always result into energy sapping, overloading of mechanical tissues and eventually musculoskeletal pain [19].

It was also deduced from the results that forty percent of respondents expressed that neck pain does not interfere with their normal life exactly but makes them uncomfortable, more than thirty percent said it interferes with their Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), which is a few percentages lower than those that believes it doesn’t interfere directly, and more than twenty-five percent believes it interferes with the Basic Activities of Daily Living (BADL), because the pain interferes to the extent that it was extremely difficult for them to perform their daily tasks effectively. The neck pain complaint may be mild to moderate in severity which may not really disturb the patients in the daily activities. That is why many participants are still coping with the pain even at work. In addition, there was no law in the nation that restricted over the counter purchase of drug especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. This gives the respondent freedom to buy pain relieving drug at any time to suppress the pain hence it cannot affect the daily activities.

It is observed from this study that the most commonly used strategy by the respondents was the conventional approach, praying and spiritual approach while catastrophizing was a rare practice among the respondents. This results slightly contradicts previous findings by [20] who reported that the chosen strategies were catastrophizing and praying/hoping. Considering the coping strategies of pain globally, [21] in their metal analysis on how the white and black are coping with pain, came to the conclusion that blacks cope more frequently using praying and catastrophizing while white uses ignoring majorly. This is due to their different religious belief that whatever happens to them comes from God. As a result of this, they prefer to seek God’s help, alongside depend on medical interventions. In this part of the world, there is proliferation of churches with strong believe in miracles especially of healing. Most of the health challenges of citizenry are pain, and it has to be noted that musculoskeletal pain including neck pain prevail more than any other causes of pain. The religious belief has contributed greatly to the usage of prayer as coping strategy for neck pain in this environment.

In addition, the study showed that sixty percent of the respondents had no barrier to accessing care to pain management, some reported that financial constraint was a barrier, a few of them reported that distance to the place of care was a barrier and others also reported that work schedules were barriers to accessing care to pain management. This explains that although respondents believed in the effectiveness of conventional intervention, they would also choose to use traditional approach, postural adjustment or ignore the pain.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that conventional intervention was perceived as the most effective method for treating neck pain. However, ignoring the pain and postural adjustments are most commonly used as coping strategies. This can infer due to distance, work schedules and financial constraints.

References

- Damian Hoy, Lyn March, Anthony Woolf, Fiona Blyth, Peter Brooks, Emma Smith, et al. The global burden of neck pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014; 73: 1309-1315.

- Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet, 2016; 388(10053): 1459-1544.

- Cohen SP. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of neck pain. InMayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015; 2(90): 284-299.

- Croft PR, Lewis M, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E, Jayson MI, Macfarlane GJ, Silman AJ. Risk factors for neck pain: a longitudinal study in the general population. Pain. 2001; 93(3): 317-25.

- Cohen SP, Hooten WM. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ. 2017; 358: 3221.

- Scherer M, Schaefer H, Blozik E, Chenot JF, and Himmel W. The experience and management of neck pain in general practice: the patients’ perspective. Euro Spine J. 2010; 19: 963-71.

- Peres MF, Luccheti G. Coping strategies in chronic pain. Curr pain Headache Rep. 2010; 14(5): 331-38.

- Turner JA, Jensen MP, Romano JM. Do beliefs, coping and catastrophizing independently predict functioning in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2010; 85(1-2): 115-25.

- Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of cognitive coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983; 17: 33-44.

- Marshall B, Peter C, Amit P & Renee F. Does Sample Size Matter in Qualitative Research?: A Review of Qualitative Interviews in is Research, Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2013; 54: 11-22. [DOI: 10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667].

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 1998.

- Lansbury G. Chronic pain management: A qualitative study of elderly people's preferred coping strategies and barriers to management. Disabil Rehabil. 2000; 22(1-2): 2-14. [PubMed: 10661753 DOI: 10.1080/096382800297079-1].

- Hadjistavropoulos HD, MacLeod FK, Asmundson GJ. Validation of the chronic pain coping inventory. Pain. 1999; 80(3): 471-81. [PubMed: 10342409 DOI: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00224-3].

- Verra ML, Angst F, Lehmann S, Aeschlimann A. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of the German version of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ-D). J Pain. 2006; 7(5): 327-36. [PubMed: 16632322 DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.12.005].

- Fejer R, Kyvik KO, Hartvigsen J. The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. European spine journal. 2006; 15(6): 834-48.

- Childs JD, Cleland JA, Elliott JM, Teyhen DS, Wainner RS, Whitman JM, et al. Neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2008; 38(9): A1-A34.

- Hoy DG, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of neck pain. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2010; 24(6): 783-92.

- Ojoawo AO, Awotidebe TO, Akindamola GA. Prevalence of work related musculoskeleal pain among academic and non academic staff of a Nigerian university. Gülhane Tıp Derg. 2016; 58: 341-347

- Kilbom, T Armstrong, P Buckle, L Fine, M Hagberg, M Haring-Sweeney, et al. Musculoskeletal Disorders: Work-related Risk Factors and Prevention. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1996; 2(3): 239-246.

- Misterska E, Jankowski R, Głowacki M. Chronic pain coping styles in patients with herniated lumbar discs and coexisting spondylotic changes treated surgically: Considering clinical pain characteristics, degenerative changes, disability, mood disturbances, and beliefs about pain control. Med Sci Monit. 2013; 19: 1211-20.

- Meints SM, Miller MM, Hirsh AT. Differences in Pain Coping Between Black and White Americans: A Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2016; 17(6): 642-53. [PMID: 26804583; PMCID: PMC4885774 DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.017].