Case report - Volume 3 - Issue 3

High degree degloving injury of the lower limb: A case report and literature review

Vives-Barquiel M1*; Oyonate H2; Hernández-Naranjo JM1; Descarrega J2; Camacho-Carrasco P1

1Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics Surgery, Clinic Barcelona Hospital University, Spain.

2Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Clinic Barcelona Hospital University, Spain.

Received Date : April 03, 2023

Accepted Date : May 09, 2023

Published Date: May 16, 2023

Copyright:© Marian Vives-Barquiel 2023

*Corresponding Author : Marian Vives-Barquiel, Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics Surgery, Clinic Barcelona Hospital University, Barcelona, Spain.

Email: vives1@clinic.cat

DOI: Doi.org/10.55920/2771-019X/1439

Introduction

Degloving injuries occur when shearing forces act parallel to the tissues, resulting in displacement of superficial layers and separation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from deep structures, such as muscular fascia and muscles [1]. These types of injuries are considered severe, with high morbidity and mortality rates [2], due to the increased risk of infections, thermal dysregulation, and fluid loss [3]. The severity of a degloving injury depends on factors such as the mechanism of injury, patient comorbidities, anatomical region, and type of injury (open or closed) [4]. Such injuries must be treated as a life-threatening emergency.

Case report

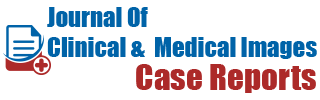

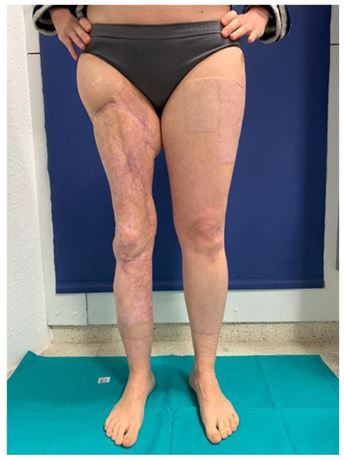

A 36-year-old woman with no prior medical history experienced an open degloving injury to the right leg and thigh, as well as an open fracture on the lateral side of the knee, after being hit by a bus. Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines [5] were applied to stabilize patient conditions. The injury resulted in bone loss in the distal lateral femur condyle, lateral patellar face, and lateral tibial plateau, leaving the articular surface exposed. No other injuries were present (figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Degloving of the right inferior limb with femur and tibia open fracture.

Figure 2: Degloving of the right inferior limb with femur and tibia open fracture

The patient was immediately treated according to open fracture protocol, and the plastic surgery team was called in. Emergent surgery was performed to remove the damaged skin and assess its viability for use as an autograft. Suitable skin was defatted to create a full thickness skin graft (figure 3). An extended tight, leg and knee joint debridement was performed removing non-viable tissues, including part of the lateral and posterior thigh muscles. A gastrocnemius flap was carried out to cover the lateral articular surface since there was no suitable coverage (figure 4), leaving a drainage. The defatted skin graft from the same leg injury was reattached. Stab wounds were made to drain seroma and haematoma from the recipient bed. An external fixator was performed to bridge the knee and stabilize the open fractures (figure 5). A negative pressure system, ranging from 80-100 mmHg pressure, was then applied to promote skin grafting (figure 6). The patient was prescribed prophylactic antibiotic therapy upon arrival, which included an initial intravenous dose of 1.5 grams of cefuroxime. This was followed by a repeat dose of 1 gram every 8 hours for three days, in addition to a daily dose of 250 milligrams of gentamicin for three days.

Figure 3: Defatted patient skin to use as skin autograft for deep tissue coverage.

Figure 4: Lateral gastrocnemius flap covering exposed knee joint surface.

Figure 5: Reattachment of skin autograft and stab incisions to drain seroma and hematoma.

After one week of admission, no signs of infection were present. The patient underwent secondary surgery to remove small areas of necrotic skin and perform a conventional skin autograft from the non-injured leg. The external fixator was removed after knee stability was assessed. The patient was allowed to perform free, controlled, and progressive knee flexion after two weeks of accident. Progressive rehabilitation therapy was prescribed and currently she achieved a range of movement 0/120º. The aesthetic result after 1 year follow-up is shown in figure 6-7.

Figure 6: External fixator and negative pressure system applied.

Figure 7: Final images of aesthetic leg.

Discussion

The skin is a crucial element in maintaining physiological homeostasis [6]. It plays an essential role in shielding the body from external forces and infections, regulating fluid balance, and maintaining thermal equilibrium. Degloving is a serious injury that involves the tearing off the skin and subcutaneous tissue from the fascia and muscles. Although it is not common, the incidence of degloving injuries has been on the rise over the past century, largely due to traffic accidents and the use of heavy machinery [7]. These injuries can be classified as either open or closed, with Morel-Lavaille being a typical type of closed degloving. Hede Yan [8] has categorized degloving injuries into three patterns: pattern 1, which is a purely degloving injury; pattern 2, which involves the deep soft tissues; and pattern 3, which includes long-bone fractures along with the degloving injury. The case discussed in this article involves an open pattern 3 degloving injury, which is considered the most severe. These injuries pose a heightened risk of infection that can develop into serious conditions, such as necrotizing fasciitis or systemic sepsis, endangering patient’s life [9].

Figure 8: Final images of aesthetic leg.

Different treatments have been proposed for open degloving injuries, but research shows that the most effective coverage for the denuded areas is the immediate reattachment of the degloved skin as a skin graft [10]. To enhance the survival of the detached skin, it is recommended to thin it into a full thickness or split thickness [11]. After defatting, multiple stab wounds should be performed to allow for drainage of seroma and hematoma [12]. Other authors suggest the addition of vacuum sealing drainage [13], which is believed to increase granulation and decrease bacterial count.

Multidisciplinary emergent management involving orthopedic and plastic surgery is critical in the treatment of degloving injuries. Extended surgical debridement, immediate coverage and bone stabilization (if necessary) is key to successful treatment.

Conclusion

Open degloving limbs are rare injuries but cases are increasing, especially due to traffic accidents and heavy machinery manipulation. They are severe lesions that can compromise limb viability or even patient’s life. It is necessary to emphasize the need of emergent and appropriate treatment performed by a multidisciplinary team. Intensive debridement should be performed, removing all non-viable and necrosed tissue. Wound coverage can be carried out by reattaching the patient's own skin (if available), thinning the skin into a full thickness skin graft by defatting it. Negative pressure system is recommended to improve skin attachment and decrease infection rate. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy should be prescribed following open fracture protocols.

References

- Stabryla P, Kulinska J, Warchol L, Kasielska-Trojan A, Gaszynsky W, et al. Degloving lower leg injury - the importance of additional treatment: negative pressure and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Pol Przegl Chir. 2018; 90(2): 5-9.

- Wójcicki P, Wojtkiewicz W, Drozdowski P. Severe lower extremities degloving injuries--medical problems and treatment results. Pol Przegl Chir. 2011; 83(5): 276-282.

- Sorg H, Tilkorn DJ, Hager S, Hauser J, Mirastschijski U. Skin Wound Healing: An Update on the Current Knowledge and Concepts. Eur Surg Res. 2017; 58(1-2): 81-94.

- Hakim S, Ahmed K , El-Menyar A. Patterns and management of degloving injuries: a single national level 1 trauma center experience.World J Emerg Surg. 2016; 11: 35.

- Cernea D, Novac M, Dragoescu P-O, Stanculescu A, Duca L, et al. Polytrauma and multiple severity scores. Curr Health Sci J. 2014; 40(4): 244-248.

- McGrouther DA, Sul. Degloving injuries of the limbs: long-term review and management based on whole-body fluorescence. Br J Plast Surg. 1980; 33(1): 9-24.

- Yan H, Gao W, Li Z, Chungyang W, Liu S, et al. The management of degloving injury of lower extremities: technical refinement and classification. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013; 74(2): 604-610.

- Sorg H, Tilkorn DJ, Hager S, Hauser J, Mirastschijski U. Skin Wound Healing: An Update on the Current Knowledge and Concepts. Eur Surg Res. 2017; 58(1-2): 81-94.

- Arnez ZM 1, Khan U, Tyler MPH. Classification of soft-tissue degloving in limb trauma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010; 63(11): 1865-1869.

- Yuan K, Zhao B, Cooper T, Jin Z, Zhou X, et al. The management of degloving injuries of the limb with full thickness skin grafting using vacuum sealing drainage or traditional compression dressing: A comparative cohort study. J Orthop Sci. 2019; 24(5): 881-887.

- Boettcher-Haberzeth S, Schiestl C. Management of avulsion injuries. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013; 23(5): 359-364.

- Yan H, Liu S, Gao W, Li Z, Chen X, et al. Management of degloving injuries of the foot with a defatted full-thickness skin graft. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013; 95(18): 1675-1681.

- Meara JG 1, Guo L, Smith JD, Genecov DG. Vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of degloving injuries. Ann Plast Surg. 1999; 42(6): 589-594.